4 High School

4.1 High School Activities

City people are more specialized, and without doubt my (city-raised) children were far better-trained than I was at any activity that they focused on. But the number of hours in childhood hasn’t changed, so the flipside of focus is that they were exposed to less variety than we were.

My brother, who didn’t especially enjoy the academic side of high school, was involved in the activities he enjoyed. He played saxophone and marched in the high school band as well as a separate school jazz band that played at basketball games throughout the winter.

He ran on the cross country team for a few seasons. His long legs made him among the best runners, and he won numerous awards.

Classes and books were a chore for him because he couldn’t see the connection to practical life. Fine, learn a few basics in history class but once you know about the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, and whatever else – who cares?

But if something had a practical bent, nobody was more focused than Gary. He loved industrial arts (we called it “shop” class) for the hands-on metal and woodworking.

His big chance came during senior year, when he was accepted to one of our high school’s “capstone” classes involving real-world projects. His project was to build a house, from scratch. Somehow the school had made arrangements with a building contractor and a developer to build a new home. They began the year by designing and digging the foundation. Then they framed it, installed the plumbing and electrical, added insulation and drywall, painted the interior and exterior, and completed the other tasks including roofing and landscaping.

The entire project exactly fit his strengths and personality and he excelled. At the time, I didn’t appreciate the significance of his achievement, but he certainly did and was justifiably proud of his accomplishment.

Generally speaking, he excelled at everything outside of school. His regular job at the grocery store gave him enough spending money to buy the necessities required of all good boys from our rural farming community

First was a car, of course. Although a new model, or even a reasonably well-running used car was outside of his budget, that was no barrier. He somehow found a beat-up, used Camaro that he could afford. Then he bought all the appropriate fixtures: new paint, interior, even a car stereo system – everything fixed and installed on his own.

The many rivers and lakes of central Wisconsin made boating an important form of recreation, so naturally Gary had to get his own boat. Somehow he found a used one within his budget and spent a winter fixing it into something we could use on the lake.

He later became interested in scuba diving, acquiring all the equipment and gaining a certification to do deep-water diving. He once joined a group that traveled to Lake Superior to look at underwater shipwrecks. On one of those dives, he was something like 100 feet underwater when his breathing apparatus failed. Fortunately, his fellow divers took the “buddy system” seriously, so he immediately was able to share oxygen with another diver and together they safely made the long rise to the surface. He commented later at how much he was shaken by the idea he was so close to death. But Gary being Gary, he immediately jumped back in the water and continued the dive safely along with the rest of the crew. He wasn’t the type to give up easily.

None of Gary’s activities appealed to me at the time, and that was fine with him. Instead I focused on various school programs. Importantly, neither of us felt pressured to do what we did – everything was entirely our own choice.

Like Gary, I was involved in the school band, and after he graduated I even borrowed his saxophone so I could follow him in his jazz band.

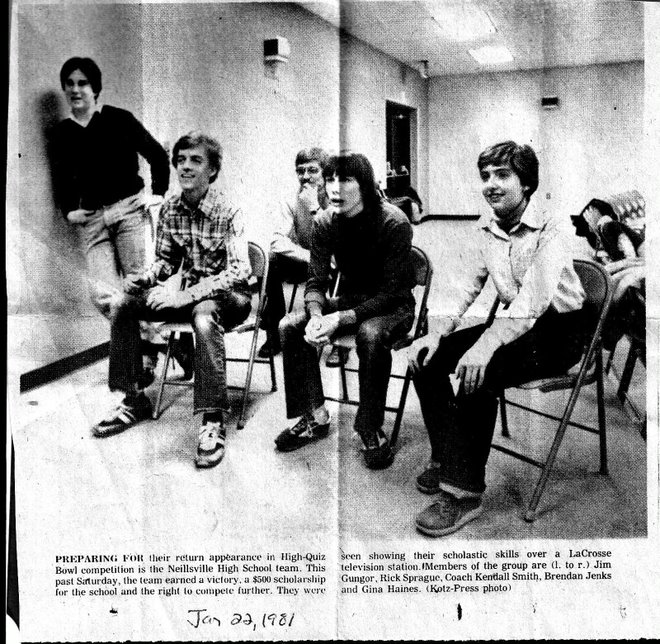

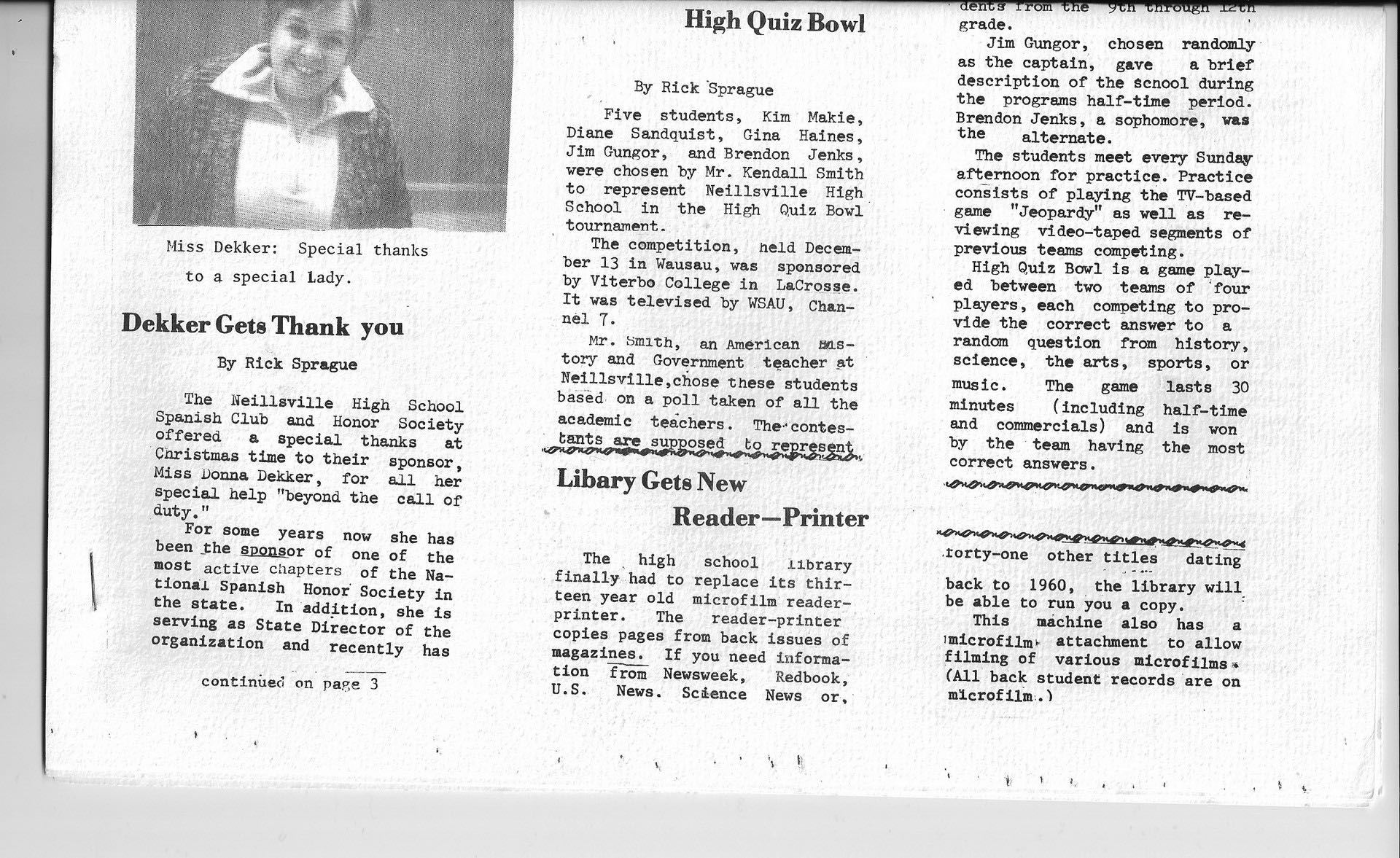

I liked writing, so of course I joined the school newspaper and soon became editor. The school yearbook was another chance at writing and I enjoyed working with the team there too.

Our school had a debate team, and both Jimbo and I were active participants, regularly traveling throughout central Wisconsin to debate other high schools.

Neillsville High School didn’t have a dedicated drama department, but we did have class plays. I was a co-star in both the senior and junior class.

On the side, in addition to all of the above, by age fourteen I had developed a passion around computers that gave me a focus to my activities and interests. I devoured every scrap of information I could, and this hobby served as a powerful motivator that had me begging my parents to drop me off at university libraries, out-of-town big city bookstores, exposing me to even more of the bigger world.

I suppose it’s natural, and common, for teenagers to feel different and left out. But I don’t remember anyone in my family feeling lonely. These activities kept us in constant interaction with others – a rich variety of people from all the town’s income levels and occupations. We may not have had swarms of people crowding around us at lunch time, but there were enough other awkward kids around that we never sat alone.

The Warrior Post

Our high school newspaper was an optional club that was organized by Mrs. Bratz, an amiable if somewhat breezy older woman who taught the typing class and a few other so-called “business” classes. Mostly this curriculum was oriented toward students who intended to become office workers, which in Neillsville was assumed to be secretarial work. Mrs. Bratz ran the FBLA club too (Future Business Leaders of America), which I think was intended to help students develop a knowledge of how businesses are run, but since nearly all the members were girls – as were the other classes Mrs. Bratz taught, like accounting – I assume there wasn’t much that was taught in an MBA curriculum.

Besides being the only boy in Mrs. Bratz’ business circle, I found myself to be reasonably good at the job. Since early childhood, books and newspapers had always interested me, and now was my chance to do something that seemed more real: what I wrote would actually end up being read by hundreds of students!

In those days, before computers and word processors, writing a student newspaper involved a great deal of tedious and manual labor with typewriters. An article would be submitted in long-hand, then carefully transcribed on one of the school’s IBM Selectric typewriters, using a technique that today would seem outrageously primitive. To print the paper in columns, each article had to be typed, by hand, in a way that inserted spaces at appropriate places within the text so that the column would be “justified” left and right. That’s a simple setting on any modern word processor, but in those days it was entirely manual. Often that would be the most laborious part of the newspaper production, and as an underclassman that’s where I started on the paper.

Mrs. Bratz was an easy-going teacher who was open to whatever suggestions the students had, so soon I was proposing and then writing my own articles: news stories, human interest, and editorials. I turned out to be one of the more prolific authors – I enjoyed writing – and in some issues my byline was on so many articles that you might as well have just put my name on the masthead.

As a high school junior, I was technically under the supervision of an editor, who was a senior, but she wasn’t terribly organized and was if anything happy to let me do most of the work. Soon I was the de-facto editor, and by senior year I was the official editor, responsible for organizing the paper, choosing the stories, and finding writers to fill in the issue.

It was then that I learned something about management as well. Although I prided myself on being reasonably good at all the newspaper tasks, it was soon clear that I simply didn’t have the time to do everything. Even with the time, I wasn’t the best at some of the other important tasks, like selling or making advertisements, and at doing the art work. At first, I tried to micromanage everything, telling the artists specifically what to draw and where it should go, but soon I learned that this wasn’t very interesting to the artists, that they much preferred to express their own creativity. So soon I was delegating bigger tasks, and everyone was enjoying the paper writing.

4.2 Church Activities

And then there was always church, the center of all our activities. My siblings and I matter-of-factly participated in all the activities, including:

Singing: we didn’t have a formal choir, but we would have been in it if there had been one. As young children, we were regularly asked to sing at special events organized for the town elder care facilities, for example).

Our church participated in a statewide competition called Bible Quiz. The format was similar to a TV game show, where contestants competed to answer questions about the Bible. Two teams, each with four or five members, sat on a long table equipped with hand-held buzzers. The moderator asked a question that would be answered by the first person to hit the buzzer. The team with the most correct answers won.

We were issued workbooks of sample questions to prepare, but the emphasis each year was on a specific book of the Bible. In our first year, we did the book of Luke. Later we did 1st and 2nd Corinthians. Although most questions were simple facts pulled from the King James Version (e.g. “What was the name of Jesus’ mother?”), to do well required careful study of the entire book.

Our church team included me and my brother, plus Jimbo and a few girls. We had a good coach who pushed us to perform well, but nobody took the competition more seriously than me. Besides the statewide team rankings, there was a separate ranking of individual players. When the scores were announced a few weeks into the competition, we learned that our Neillsville team was among the best in the state – and I was ranking number one among hundreds of participants. This only drove me to prepare harder, and by the end of the year, I had essentially memorized all the books.

Scouting: we had an alternative to Boy Scouts that amounted to much the same thing, and we participated in innumerable campouts and service projects.

I’m not sure why our church felt the need to organize its own alternative to Boy Scouts, since back then the Boy Scouts of America was itself quite religious by today’s standards. Ours was called “Royal Rangers” and we had our own uniforms, scouting manual, and achievement badges. I suppose the Boy Scouts, which had to appeal to multiple religious denominations, wouldn’t have been able to go as deep into Bible instruction as we did. It really was a different age.

4.3 Sports

I’m grateful to my father for an important decision he apparently made in college. His own father had been a fan of organized, professional sports: baseball, football. But Dad thought that was a complete waste of time. “If you’re going to play,” he said, “Play. But don’t watch others play.”

Thanks to his leadership, we felt free to ignore sports, despite the interest shown by my friends, like Jimbo, who through elementary school was an active participant in little league, and who afterwards followed football and baseball closely as a fan. Even John Svetlik, who like me never pretended to be athletic, lived in a family that watched sports on TV, something we never experienced.

As far as formal sports participation goes, my brother was the most athletic: during his freshman year he joined the school cross country running team. He must have done reasonably well – I vaguely remember some award ribbons lying around the house someplace.

I was even less interested. Nevertheless, our summer visit to the Air Force Academy convinced me that for a successful college application I would need to show some interest in sports. During middle school, I had been on a swim team, but there wasn’t one for high school. Maybe I could join track and field, like my brother, but that seemed like a lot of work for nothing. So which sport would I put on my resume?

The most important sport in a small town school is, of course, football. Blessed with tough farm boys eager to prove themselves, the team was quite competitive. A few years before I entered high school, Neillsville had even won the state championship. The annual football Homecoming Parade was the biggest event of the school year, drawing participation from the entire community. If I really wanted to prove myself, football was the place to be.

Of course, the one detail is that I was woefully unqualified to play football. A scrawny kid who dreamed of someday weighing more than 100 pounds, I was already a target from tough kids who wanted somebody to pick on; you can imagine what would have happened if I found myself on a field opposing a team that really wanted to beat me.

Sometime after my freshman year, I discovered that the football team needed helpers, people to help track and carry the equipment, organize the trips to out-of-town games, and ensure there were other supplies, like snacks and water. The politically incorrect term is “water boy”, but on my college application forms I proudly wrote “manager”, which was the term used by the coach to recruit kids to this often thankless task.

As the water boy, er, manager, I attended every practice and game, home and away. I knew all the players and worked daily with the coaches. I didn’t mind the pejorative aspects of being called the water boy, because for me this was just a necessary line in a resume that would get me into a good college. That was the motivation that drove me.

One bonus was that I was issued a team jersey, like the players, and I was therefore allowed to wear it on game Fridays, when it was a point of pride for the boys on the team. I felt like I belonged!

The job also demanded a certain level of responsibility, something that ordinarily I could be trusted to handle. But I was young, and weak, and eager to please everyone, and this is when I got into trouble.

One of the boys on the team, a kid who was not an especially good player, decided that he liked some of the equipment, especially the team jerseys and he determined to steal some if necessary. Since I was in charge of the supplies, he knew he would have to get through me, so he began to befriend me in a half-threatening, non-transparent way. He mixed the carrot and stick: on the one hand he liked me because I was such a cool guy; but on the other hand, if I disappointed him by not letting him steal the equipment, then it was clear that I wasn’t a good friend and might even deserve to be treated like an enemy.

I ignored his entreaties as best I could, never stating clearly that I wouldn’t help him, while never fully agreeing with his plan either. Eventually this produced what I learned was the worst of both situations: by egging him on, I prolonged his attention, but by not producing results I made him more frustrated. Eventually it came to a head and he cornered me in the locker room to demand that I get him the supplies right then.

I don’t remember exactly what I did or didn’t do. I doubt that I would have simply handed him the equipment, or even that I would have looked the other way while he pillaged the storage room I was supposed to protect. I don’t think I would have been that obvious in my sin. More likely, I simply wasn’t as vigilant as I should have been, and he found an opportunity sometime where he could sneak in without my knowledge. There was a lot of equipment to track and it wouldn’t have been unusual to lose a piece or two. I probably convinced myself that he didn’t really steal it and that it would turn up eventually.

Fortunately the football coach wasn’t so easily fooled. Somehow he knew that this kid was a troublemaker, and when equipment turned up missing he immediately charge the obvious suspect. “If I ever catch you wearing that shirt, I’m going to rip it off you right in front of everyone,” he said. I never heard more about it.

Looking back on the incident, I wish I had been more forceful from the beginning, more straightforwardly obvious that I was not the type who would allow a crime like this to happen. It was a good lesson, though, and I’m glad I learned it in high school rather than suffering through it later in life, when it would have caused more damage.

4.4 Mexico

Later in high school, my grandmother’s death left our family with some extra money that my mother thought would be well-spent on forcing me to do even more with Spanish. She enrolled me in a missionary trip to Mexico during the summer after my sophomore year, and this trip opened my eyes to the world of languages and foreign countries in ways that were as impossible for me to appreciate at the time as I now recognize it was important for my future.

The trip was organized by some missionaries who were associated with a church in Madison Wisconsin. It was to be a whole collection of firsts for me. My first jet airplane ride, my first view of the ocean (of the Gulf of Mexico, which I saw through the window), and of course my first visit to a country where people didn’t speak English.

I turned out to be one of the few trip attendees with a basic knowledge of Spanish. Other than the missionary himself, who had lived there for many years, most of the team didn’t know any Spanish at all, so it was fun for me even with my limited ability to count or enunciate a few basic thoughts.

One of the adults, a middle-aged man with an impressive handlebar mustache, was one of the first people I’d ever met who had a PhD. Somehow perhaps he was taken with me because I remember him giving me some side advice: remember that you can go to a good school and come out without losing your religion. At that moment he became somewhat of an influence on me, both because he left me with some curiosity about his warning (why on earth would you think I might lose my religion?) and some assurance that it was possible to turn out fine, like him.

After arriving in Mexico, we did some sightseeing in Mexico City and I saw for the first time a truly, terribly polluted city. Back in the 1970s, there wasn’t as much air pollution as today, but even then we thought it was horrible. We travelled on the subway, visited markets and shopped for trinkets.

Later we took a series of minibuses up into the countryside, through some mountains, down some rugged roads to the town of San Luis Potosi, and I loved it. Everything was foreign and new to me. Until then, the biggest city I’d ever visited was Minneapolis, and really that was just the suburbs. I’d never travelled on a subway (or for that matter, any kind of mass transit including a bus). All of this was for the first time.

Until this trip, I had exactly two experiences with “Mexican” food. The first was at a church-related function at a friend’s house long ago, when the hostess made “tacos”: ground beef served in a home-made wrapper that resembled a pancake more than a tortilla. My second experience was at an Eau Claire fast food restaurant called Taco John’s, an early imitation of the Taco Bell chain that was just becoming established in other parts of the country. So when, at our hotel, I had freshly-made tortillas for breakfast, and later we were served pork-filled “flautas” and more for our meals – the fresh flavors were heavenly.

We were surrounded of course by the Spanish language, and to my surprise I found myself able to get around even with my basic vocabulary. All those words I’d learned in class were suddenly useful! But I also drank a large dose of humility upon realizing how different this was from the classroom. No matter how great I thought I had been as a student, I was nearly unable to understand the important things around me, and expressing myself was even harder. So although it didn’t seem as easy as I had naively believed before coming, I was able to see that through some effort, learning a foreign language was something that would be doable and enjoyable.

Part of our experience was going door-to-door, visiting every home as missionaries. Divided into teams of three, we were issued tape recorders with a short Spanish-language message, and I was assigned the role of memorizing a Spanish phrase that meant “Would you like to listen to an important message on this tape recorder?”

The villagers were generally pretty friendly, and we were often invited into people’s homes, though I realize now that this was probably more their curiosity of seeing American teenagers than it was out of a particular interest in our message. Still, the experience brought us into contact with the real lives of ordinary Mexicans, as we were welcomed into the tiny kitchens and one-room homes of the villagers. In one house, I held my tongue as a small rat rushed past, right behind the girl in my team, a city girl who if she had known what was happening would no doubt have begun screaming right there.

We were traveling in a part of Mexico in the mountains far from the coast, but it was hurricane season and during part of the trip it began to rain heavily, with ferocious winds. A piece of patio furniture in our hotel was thrown so hard across the patio that it shattered the window of one of our rooms.

The streets became flooded, waist deep in ways I’d never seen before, and we wondered why that would be: how could a Mexican town have streets filled with so much water that the sewage system couldn’t handle the load? This was something that never happened in even the smallest, most seemingly disorganized town in Wisconsin. Clearly the answer had to do with the terrible poverty of these people who were living in ramshackle huts, moving about often without cars or trucks, riding draft animals or occasionally bicycles. But the question for us was whether poverty caused the poor response to flooding, or was the regular flooding in a place like this one of the reasons for the poverty?

Traveling with missionaries – the same, fundamentalist evangelicals I was familiar with at home – kept a thread of the familiar throughout my experience in Mexico, so although I was shocked to witness, for the first time, so much that was different from my life at home, nothing I saw presented a significant challenge to the beliefs that I had already formed about the world. I was surrounded too by serious Christians who, like me, insisted on regular prayer multiple times per day with close reading of the scriptures. Our every move carried with it the ever-present background sense of a personal God watching and directing us.

If I ever became lost or uncertain about something in Mexico, I knew that God – through the Holy Spirit – would direct me back to where I needed to be. So although, especially in the cities there seemed natural cause to be wary of danger like criminals or spoiled food, we passed through unscathed and unshaken, believing that our lives were in God’s hands, who would keep us safe.

And of course that’s what happened. We returned safely home a few weeks later, but with a bit more understanding of the world beyond me. I also had made several friends in Mexico, and we exchanged letters for another year or two after that. I was now firmly and permanently interested in foreign cultures.

4.5 Vacations

I remember the first time I stayed in a hotel, or more precisely, the moment I first became aware that hotels existed. I was very young, probably less than five years old, and we were somewhere in the Blue Hills of northern Wisconsin, the place where my parents had spent their honeymoon. I don’t remember why we were there, but it must have had something to do with my father’s family, because his parents (my grandparents) were there and they were staying in what to me seemed like a luxurious cabin, with a front porch and many conveniences. My family, on the other hand, was loaded into bunk beds on a concrete floor. I don’t know why I remember this, but it was an early memory of thinking how poor we were relative to my rich grandparents.

Hotels and motels remained a luxury to my family throughout my childhood. We stayed in one again at my uncle’s wedding, held in far-off Madison Wisconsin. Later I was told that, due to a terrible sickness of one of my siblings, the time in that hotel was no happy memory for my mother, but for me it represented something exciting and new, helped considerably no doubt by the TV set in the room and the appearance of the cartoon show Underdog, which we enjoyed immensely.

Mostly when we traveled far from home, we stayed with relatives. On the rare occasions we traveled through areas without people we knew, we camped in a big family-size tent.

We knew tent camping well. During the summers, we usually attended a weeklong family Bible camp, held at Spencer Lake, near the small town of Waupaca, a few hours drive East of Neillsville. Our tent was surrounded by other families in tents and RVs, our days spent enjoying swimming at the beach, grilling food on our Coleman stove, and attending religious meetings late into the evening.

4.5.1 Going West

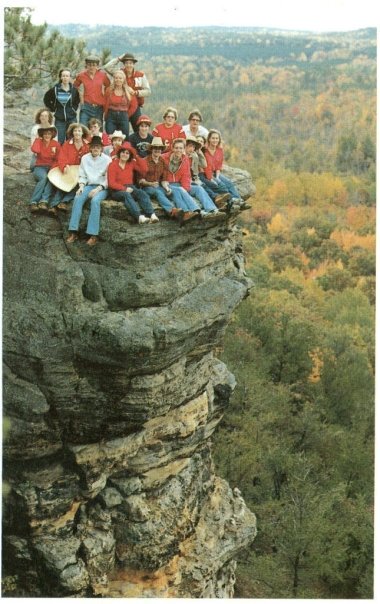

But our first big vacation happened when I was seven or eight and my father decided to take the family to a religious meeting in the Shiloh Valley of Montana. The drive would take twenty or more hours, which we split into three or four days along a route that took us first through the familiar geography of Minnesota, then along to North Dakota and the plains, ultimately rising to the mountains and “big sky country” of Montana.

To seven-year-old eyes, the wide open spaces of the American West seemed like a magical, foreign land. Traveling in a station wagon, the iconic family vehicle of the 1970s, everything seemed spacious and free. With a “top” on the car roof that contained our tent and a week’s supply of provisions, we stayed each night at (cheap) family campgrounds along the way. My mother prepared sandwiches for lunch, and heated canned soup and vegetables for dinner. The better campgrounds boasted hot water for showers and occasionally a swimming pool for recreation. What more, I wondered, could life offer?!

At Shiloh itself was another campground pierced by a cold, mountain stream and fishing, which my father enjoyed and which produced more food for dinner. I don’t know what sort of budget my parents planned for this trip, but in today’s money I’m sure it would seem trivial. As a child, it never occurred to me that, instead of the homemade sandwiches, we might have eaten at fast food restaurants or stayed at cheap motels – those were luxuries beyond contemplation. Stopping in the beautiful natural places along the way – Mount Rushmore, the Badlands, the Rocky Mountains – it’s not clear to me now that we would have known more fun at the far more exotic places like Disneyland that many other children associate with vacations.

Our trip to Montana was the first of many summers we spent traversing the West. My father seemed unaware of other compass points, because whenever we thought about family vacations, it was always to the Great Plains and beyond, to the Rocky Mountains. Sometimes we started on a southerly route, to Iowa so we could stay with my parents’ lifelong friends, Arnie and Joyce Cox and their children. In sleeping bags on the floor of their living room, it never occurred to us – in fact, it would have seemed cold and almost rude – to stay anywhere else. Obviously if we come all this way to see somebody, we’re going to stay at their house; otherwise what’s the point?

One year we travelled to Colorado, at first to Denver where we saw the childhood friend of my mother, who now lived there as a suburban housewife. We weren’t invited to stay with them, and in fact the whole visit seemed more stiff and formal than I was used to, not nearly as fun and interesting as the visits to our relatives when we stayed overnight.

After Denver, we traversed the state to spend several days in Grand Junction to visit my great-grandmother and father. They lived with my father’s aunt Avenel and her husband Howard, who was a real estate developer. He bought large tracts of land outside the city, which he divided into subdivisions traversed with roads and single family homes. Along one of those roads, at the end of a cul de sac, he built a large compound for himself and his sons, who followed him in his business, and an adjoining house where my great-grandparents lived.

Vacations to me were always like this: a destination, visiting people along the way, learning new things about family and friends as we went. The stories I heard from my great-grandfather cemented my interest in this kind of travel and in maintaining an eternal optimism, a lust for the wonders that await every new adventure away from home.

4.5.2 Canada

Growing up in rural Wisconsin, it was only natural to spend summers outdoors. Although my family wasn’t nearly as hard-core about it as others, who lived for hunting and fishing, we did our share of camping.

To us, an ambitious camping trip involved a lengthy drive north into Ontario Canada, known for its plentiful and under-fished lakes. On at least two summers, my grandparents brought Gary and me along with them.

We stayed for about a week in a backwoods location, carrying all of our food and supplies, including a canoe strapped to the top of Grandpa’s car. Rowing out onto the endless lake, we eventually docked at a small island where we set up camp for several nights. Although we carried plenty of backup food, our intent was to live on the fish we caught.

I remember being disappointed at the poor catch and mostly eating the ham and turkey slices in our cooler.

4.6 Girls

I had a mother and a sister, grandmothers, as did most of my friends. There were women and girls everywhere, so if to understand women requires first-hand experience, then I have no excuse. I failed.

By the time I entered my early teens, my friendship with Jimbo began to fade as we developed different interests. I still saw him regularly at church, of course, though this was becoming mostly a Sunday morning thing, as his other activities kept him busy the rest of the week.

One of his biggest activities was girls. One summer in high school, his parents sent him to a camp at Illinois Wesleyan, a college in Bloomington Illinois, coincidentally the same town where my cousins lived. In a psychology class he took, he was diagnosed as being exceptionally interested in girls. I guess his hormones were raging.

His stories were interesting to me partly because they seemed to tell of an unknown world, one full of adventures I couldn’t understand because they were so unfamiliar. Partly this was due to his natural assertiveness and ability to talk freely to anyone. Many girls may also find attraction in self-confidence, which he had in large measure: he carried himself in a way that implied dashing and charm, a sharp enough contrast with my nerdy personality that perhaps he needed to dial down his relationship with me.

Still, I was interested in trying. Summer Bible camp was the ideal place to experiment. Jimbo and I were there for a week together, and although the rules naturally kept respectable distances between the boys and girls, there was plenty of time to mingle during mealtimes and at camp activities.

Jimbo took full advantage of the opportunities and within the first day had already selected a target or two, and was well on his way to pairing off.

I realize that to modern ears, this story may seem hilariously quaint, but in those days of Camp the thing to do was to get a girl to sit next to you in the evening church services. There wouldn’t be much opportunity to talk in the service itself, but afterwards there was plenty of time to walk her back before curfew to the border that separated the girls and boys’ sides of camp.

Since Jimbo was generally lucky enough to have a companion within the first day or two of the week, I was left to fend for myself, sitting alone for the service unless I took matters into my own hands and found the nerve somehow to ask a girl for myself.

So it was, with herculean effort on my part, that I chose a target and by Thursday was ready to ask her to join me at the nightly service, and to my surprise she agreed – provided she could bring one of her friends. No problem I though, and in fact it worked out great because now Jimbo was happy to be seen with me, now that I had a girlfriend too, so we all sat together.

I thought everything went well. I was very polite, of course, and after the service walked the girls back to their side of the campground without incident and being very gentlemanly the whole time. Relieved that I had conquered my shyness enough to have an actual girlfriend, I was looking forward to the Friday night (and final) service when I’d get to repeat our encounter.

Sadly, it was not to be. The girl informed me, via her friend, that she was not ready to be seen with me again for the Friday night service.

“She has a hard time concentrated on God when you’re around,” her friend confided to me. That was the last I ever saw her.

Perhaps expecting (hoping?) that my siblings and I would have more success in the dating game, my father decided sometime when I was in middle school that our family should set specific rules for boy-girl interaction. By clarifying these rules upfront, he hoped to head off any conflicts that might arise later. He wanted to specify the ages at which we would be permitted to date.

That I no longer remember the rules tells you that Dad’s concerns were unwarranted. If anything, we probably could have benefited from tips on how to be more aggressive in finding girlfriends.

With so much of our social lives consumed with church-related activities, our choices were already pretty limited, mostly to the opposite sex siblings of our friends. Yes we occasionally attended events with other churches where we might meet new people, but opportunities for interaction were brief.

I wanted a girlfriend, but it wasn’t until much later that I learned how unlikely I was to get my wish. It’s not because I was undesirable; I’m pretty sure there were girls out there who secretly thought about me. But despite having a sister, a mother, and being surrounded by girls at school and church, I lacked the confidence that is a basic requirement for a boy who wishes to get a girl’s attention.

As always, my experiences contrasted sharply with Jimbo, who always seemed to have a girlfriend. It was not until years later that I learned how many girls he had been seeing. He had access to his parents’ car, which certainly helped, and I remember once riding with him all the way to Minneapolis to meet a girl at the airport, someone he had met over the summer. Meeting her at her airplane gate, he kissed her, on the lips, in front of me and everyone else! Looking back, I assume I was there as a chaperone, a parental requirement intended keep him in line. We met her, drove her to her destination (I assume it was a relative nearby) and then we went back to Neillsville. That was it.

In the 1970s it was still possible, even common, for a public figure to be ostracized for what in those days we would have called sexual immorality. In today’s world, where I don’t think those two words can go together (is there a such thing as immoral sex?), the assumptions under which I was raised are described as “traditional”, a word that carries tinge of oppression, like a background pall in the air that suppresses us from living full, free lives. But I didn’t feel oppressed, or restricted, and I don’t think my friends and family felt that way either.

“Oh, well you were a white boy, so of course you had it made!” is the standard view today, but I think that’s a simplistic, naive way to describe a society where everyone, including white boys, had both freedom and responsibilities, expectations that, when fulfilled made all of society better off, but brought swift trouble when unmet.

In our simple, farmer-based perspective, the needs and desires of boys and girls were treated not much differently than the way the community treated the needs of cows and bulls. The innate differences between the two sexes was so obvious as to be unworthy of debate.

Of all the immoral sins, sex outside marriage was among the worst. Today it’s hard to watch even the most “family-oriented” movie without seeing teen sex as a normal, healthy part of growing up, but in my memories the very idea was shocking, and I internalized that attitude. It was unthinkable to me.

That said, of my graduating class of a hundred kids, at least half a dozen girls were married or pregnant.

At least through high school, my brother had no better luck than I did. But he had money, and a car, so girls were definitely interested in him. Like me, he simply lacked the self-confidence to put his charms to use.

Everything revolved around our church. The youth group was split equally between boys and girls, and I’m sure the girls were as interested in us as we were in them.

One highlight of our church youth activities came at regular outings to the big city of Marshfield and its roller skating rink.

My brother and I were both tall and lanky, he more than me, and being relatively unathletic we were somewhat at a disadvantage on roller skates. But it’s also not an especially difficult activity, so we learned and we were okay.

But once or twice during the evening, the rink operators would turn down the lights and play a 70s love song. Boys were encouraged to invite the girl of their choice to join them on the rink and even – gasp – hold hands. Awkward as this was to a shy boy like my brother, somehow he always managed to find a partner. They would skate around a few times during the song, hand in hand, and then it would be over.

Sorry, but that’s pretty much it for the gossip.

4.7 Svetlik

I developed a competitive spirit for school early, from second grade when the teacher used a scoreboard to track which kids were doing best, to fourth grade and the contest for who could read most books, to fifth grade when I competed against the smartest girl to see who was best at class assignments. And always, there were the regular chess matches with Jimbo. In each case, I was inspired to try harder as I discovered how I could always win, with enough effort.

It wasn’t until seventh grade, when a new boy moved to town, that I met the first person I felt was truly smarter than me in every way. Our initial rivalry quickly gave way to a deep friendship that ultimately influenced me more than any other.

I first heard rumors about John Svetlik near the beginning of the year when other students, by now accustomed to my role as best in the class, told me about another boy who was also always first in his class. He was so good at math, they claimed, that our teacher Mrs. Reidel exempted him from normal classwork to give him a different textbook and assignments.

He came to Neillsville from a town in New Jersey with an unpronounceable name but which we assumed was the Big City compared to Neillsville. Although he was new to us, his grandfather had been here decades, operating the Ford dealership in town, which his father would now be running. He had a little sister named “Sam”, short for Samantha, and they lived in a new house on the other side of town to us but near the school.

John’s family were good Catholics, which meant that our non-school free time never overlapped. My evenings and weekends were full of my own church activities, but school was another matter. As the class overachievers, we shared the common fate of nerds everywhere of being ostracized at lunchtime and it was natural for us to begin meeting every day at school. Our middle school had begun to divide into the “popular” kids versus the rest of us, and in particular there was a small but dangerous group of athletically-minded bullies who were known to gang up on those of us without enough social skills to avoid their oppression. As one of the new kids, and nerdly to boot, John came under the same scrutiny that we did and we soon were forced together for common defense.

He knew so many more things than I did, so he introduced me to many wonderful new subjects I hadn’t imagined before. Science fiction! He had me reading Asimov and Heinlein, and we shared stories about new scientific discoveries and the whole wonderful world of technology. He knew about electronics, and was good at it, showing me and then teaching me how he made circuit boards, how he modified his home clock radio to brighten the display automatically in the light, and much more.

Our friendship always had a slight edge of fun competition, but through it all I remembered my previous place as the smartest kid in class. It was an important part of my identity, to be the best in class. If I couldn’t be as athletic as others, or as popular, I wanted to be different and better at something and that something was academics. But John was so much better, I learned, just so innately smarter and more capable, that I discovered my only option was to admit defeat and find some other way to differentiate myself.

It didn’t matter. John exposed me to such amazing new worlds of ideas and I was honored – humbled – to be his friend. Along the way I learned that wonderful feeling of discovering something interesting that appealed to him too, things he hadn’t already seen. I devoured new magazines and books, always looking for something I could show to John. If I couldn’t be better than him, I could at least be first.

I also discovered that, despite an intelligence that compared to mine seemed superhuman, he was still capable of mistakes. The effortlessness with which he beat me at academics, I noticed, left him prone to be a bit lazy, and that was where I had my edge. If I applied myself – really focused on a math problem or a feat of memorization – and if along the way he grew bored or distracted by something else, I learned I could win. It was a lesson that became one of my most important lifetime observations: the truth of the turtle and the hare. Focus and determination, I learned, can beat innate ability.

Like me, John was often treated like an outcast, a nerdy boy distinguished by not being particularly athletic or popular with the other students. One day in eighth grade, Billy Roberts used John’s lack of social skills as an opportunity to put him in his place, and without provocation began to make fun of him between classes.

John immediately began swinging, hitting Billy Roberts as hard as he could with his fists shoving him to the floor, beating and kicking him. There was no particular damage, but of course John was called to the Principal’s office.

The Principal called me in too, and as I sat in front of him at his desk I began to cry. I hadn’t done anything wrong, I insisted.

“It’s okay,” said the principal, “You’re not in trouble. We just wanted to talk with you because you’re friends with John and we want to hear more about what happened.”

I didn’t know much, so after a few questions I was let go.

John wasn’t at school the next day, a Friday, expelled for a day of punishment. On Saturday I went to John’s house to see more of what had happened.

John’s Dad met me at the door. “We’re so proud of John, for sticking up for himself. Yesterday we let him do whatever he wanted at home.”

John was beaming too. This one incident took away all possibility that other kids – those who were much meaner than Billy Roberts – might treat him as a pushover. It still didn’t classify John as one of the tough kids – he would always be a nerd – but to anyone considering a little fun at the expense of a weaker kid, there were much easier targets. John was securely out of range of the class bullies.

Ironically, John’s biggest influence came when, sadly, his family moved away from Neillsville the summer before tenth grade. At fifteen, I was just beginning the most rocky years of teenagerdom, and my friendly competition with John was expanding beyond schoolwork and hobbies, to the broader worlds of socialization, of popularity, of girls. As the two indisputable representatives of the Neillsville High School geek elite, I needed him as an ally and as proof that I wasn’t alone in my interests in computers and the future. His leaving suddenly turned me into a loner.

Jimbo was still a friend, of course, but becoming increasingly distracted by girls, and by his friend Tracy, the only child of divorce we knew, a boy whose father lived far away and whose mother was proud of her independence and free-thinking ways, who gave Tracy his own phone and a subscription to Playboy to complement his education. Tracy was a neighbor, and we were friendly too, of course, but he was really a better match for Jimbo. Both boys were sports-watchers, for example, intensely interested in baseball. I couldn’t keep up, and until John left, it didn’t matter.

Now suddenly, with nobody else to share my competitive love of computers and technology, I felt very alone. It was around this time that I began to write, first for myself, and then letters to John, who to my delight wrote back promptly and at length. Thus we began a long, fruitful correspondence whose impact I feel today.

Our first letters were less noteworthy to him than to me. He was adjusting to a new, much bigger city (Mesa, just outside Phoenix) and a new school (a private, Catholic school) and his descriptions of his new, urban world were to me a wonderful window to a vast, unexplored territory that I wanted to see too. With every letter, I learned more about how different it was outside Neillsville, and nearly all of it to me was exciting and worthy of envy. He told me about the computer store near his house, the big shopping centers, the bookstores, and even the university campus. I was both envious at his great urban experiences and emboldened at the thought that someday I too would be able to enjoy that type of life if I chose. He opened a completely new world for me.

Since we were already good friends, we were comfortable discussing more personal thoughts. As it became clear that the distance between us ensured that neither of us was in a position to leak secrets, our letters took on a more intimate tone, spilling thoughts and dreams that might have been more difficult if we were living in the same place.

He told me about high school crushes, beginning with innocent teenage unrequited relationships, situations I could relate to. But over time, as he became more emboldened, both in his actual life and in his willingness to express himself in letters, he divulged more details about experiences that were beyond my social abilities at the time and I learned far more than I would have if he had been living near by.

Some of his stories shocked me, both as a small town boy and as a deeply religious one. John knew of students who used drugs, fooled around sexually, drank alcohol, a teacher who talked openly about a gay lifestyle. These weren’t themes that I encountered in Neillsville other than as theoretical concepts that proved Satan was out there in the “world”, trying to deceive us, threatening chaos and all that would be wrong if we slip from our religion.

Coming from John, though, these stories took on a reality that, though at first disturbing, helped introduce me slowly to a bigger, more diverse world, and prepared me in a way I don’t think could have happened without such a faithful, long-distance correspondent.

Writing helped, too, because I was forced to put into words, to express on paper my thoughts, and having John as a confidant was a reassuring way to know that, in the difficult transition to adulthood that we all make, I had a friend who was truly listening.

4.8 Senior Year

Today I would be considered a nerdy boy, socially-awkward.

Although I certainly wouldn’t have won any awards for “most social”, I think it would be hard to peg me as shy or reserved during my final year in Neillsville.

I had friends. I was active in school activities. Nobody would have voted me “most popular”, but in a class of fewer than 100 kids, I knew everyone, and everyone knew me.

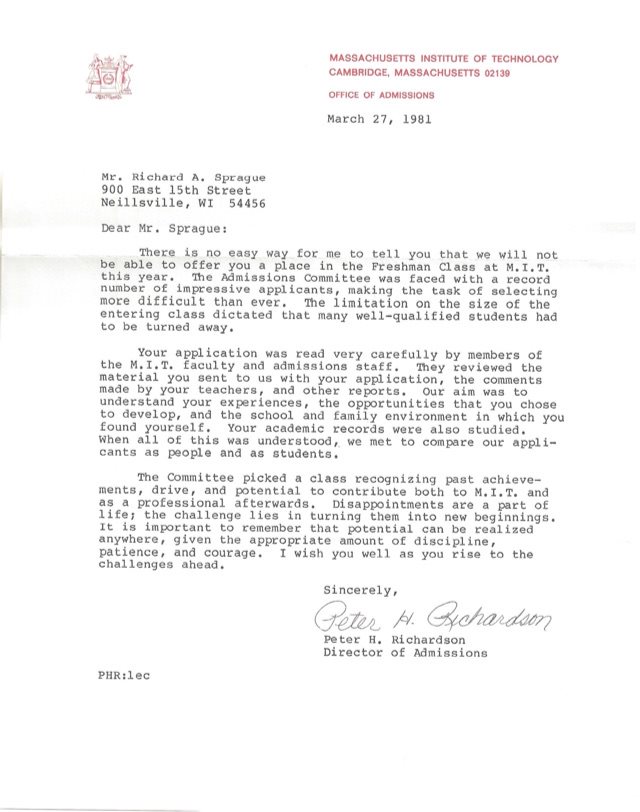

College Applications

During the fall of my senior year, I was busy with college applications. Today’s kids use terms like “safety school” or “reach”, and they confer with guidance counselors and college consultants to pick the right combination of prestige, selectiveness, geography, and personal fit.

Among my high school and church friends, college seemed very optional. Only a few of our parents had attended college. My father, like our school teachers of course, had a bachelor’s degree. But among the farmers and small businessmen who made up our community, college was at best an optional luxury and for many it seemed like a waste of time. Unless you’re planning to become a doctor, or some professional that requires the degree, what’s the point?

This general attitude meant that there was little or no pressure to apply to colleges. Everyone was supportive to any student who wanted to go to college, but our parents and community were supportive of other choices too. Trade school was a common option: a year or two of study could qualify you as a plumber, an electrician, a welder, a secretary – perfectly acceptable ways to earn a living. If you had a family or relative already in one of those businesses, you could skip the school completely and simply learn on the job.

But I wanted to go to college (Section 3.7). I liked school, I was good at it, and thought nothing would be more fun than to learn more in-depth about so many of the exciting ideas, especially about the computers and technology that I was already learning on my own. I can’t underestimate how important it was that, meanwhile, my close penpal relationship with John Svetlik was shaping my choices. When John told me about how he’d like to attend one of the major schools, like Stanford, I took him seriously. I wrote to the colleges myself to ask about the application process. I borrowed books from our guidance school library that explained the SAT testing process. Books that included rankings appealed to my competitive spirit, and it was natural for me to ask why not go for the best.

I applied to exactly three schools:

- Stanford University

- MIT

- University of Wisconsin - Madison

Each application was completely different from the other. Long before the introduction of today’s “Common App” and other standardized processes, the written applications required different letters of recommendation and different essays. Except for my MIT essay, which I wrote on a typewriter, all of my applications were handwritten in ink.

Madison was my “safety”. As an in-state resident with good grades, my admission was all but guaranteed and I didn’t even consider the possibility that it might not happen. If anything, I assumed this was the most likely scenario, and I even had friends who discussed informally the possibility of possibly living together while there. My father had attended for a year, and of course we had visited the city a few times so it felt very doable and real.

Looking back, I’m not sure I understand how I came to apply to the other schools. Our high school library had one of those books that ranked colleges by their selectivity, including test scores. I didn’t have SAT results when I began the application process, but I assumed I was well within their acceptance range. I knew from my competition with John Svetlik that I wasn’t the top of the top, but there’s always a chance, right?

So I wrote letters to Stanford, and then MIT, asking them to mail me the application materials. I absorbed every page they sent me. Even today I remember the sepia colors of that Stanford booklet, with its pictures of palm trees and happy-looking students. The MIT catalog, with its focus on technology and hard-core science: I loved it even if, unlike Stanford, it was accompanied by wintry photos of a campus covered in snow.

MIT required an in-person interview, an hour’s drive to the bigger city of Wausau. My long-suffering parents took me there at the appointed time and I met an elderly man who engaged me in an informal chat in which I think I did reasonably well. But he ended the interview with a nonchalant question about which other schools I was targeting and which was my top choice. “Stanford,” I replied innocently.

So perhaps it was no surprise that in March I received my first rejection letter.

The letter arrived on a particularly dark day, along with news of the assassination attempt on President Reagan. The hopes and dreams I had established for myself seemed to be colliding with reality.

Exactly one week later, mother picked me up from school and on the ride home she mentioned that I had received a letter from Stanford. I had already braced myself for the inevitable rejection, but then she added another detail that hadn’t occurred to me: “It’s a very thick envelope,” she said.

Graduation

By the end of my senior year, I finally felt adapted to the Neillsville social environment. In a small school, everyone knew me, but through my accomplishments and my involvement in their lives, I discovered that I had more personal relationships than previously I had thought.

I had never been particularly stressed about grades. I could get A’s just by paying attention in class. People, including teachers, thought of me as the class brain, so on the one hand I guess I had something to prove, but on the other hand, I was often left alone. The bottom line is that Neillsville wasn’t an especially challenging place academically, so there was little or no pressure to go above and beyond the minimal requirements. I didn’t pay too much attention at the time, but I suppose probably the bottom half of the class was pretty poor academically, so it may not have been all that hard to shine in a place where the bar wasn’t particularly high.

You’d think that in that environment, achieving valedictorian status would be a slam dunk, but no: that honor went to Gina. The number two salutatorian spot went to another girl, whose name I barely remember. The GPA calculations that determined class rank included the grades from physical education classes, in which I had never scored an A, and more often than not was a B. My final GPA was something like 3.85.

Anyway, by graduation time I had already been accepted to my dream school and these honors no longer meant anything to me. Probably I was also plagued by a touch of arrogance, a lifelong affliction that caused me to feel and act like I was better than these kids and therefore didn’t really care which awards they won.

That said, I would have enjoyed giving a speech at graduation, but alas the honor fell to others. Gina was a quiet, somewhat soft-spoken girl, the daughter of our home economics teacher. Non-intuitively for somebody who had never been involved in sports, she chose as her valedictory speech a theme about football, something about competing to win, or advance the goal, or – I really don’t remember. The number two person also got to say a few words, and the rest of us, the top ten, were invited to sit on the main stage looking on behind them. I sat next to Jimbo, who chuckled when I held up a “Hi Mom” sign to the audience in front of us.

4.9 Leaving Neillsville

West coast colleges, including Stanford, run on the quarter system, with three periods per year instead of the two semester system of most midwest schools. That pushes the first day of classes almost a month past the start dates for all of my college-bound Neillsville friends, who by August were already beginning to pack their bags and say their goodbyes.

I found myself officially invited, for the first time, to honest-to-god parties organized by my high school classmates. Many of us had already turned 18, the legal drinking age in Wisconsin at the time, so the invitations came with the implicit assumptions that beer would be served, along with whatever potential debauchery might ensue.

Fish supposedly are unaware of the existence of water, living so immerse in it that anything else is incomprehensible. Neillsville was my water, and I was that fish, but I was eager to leave and learn all about the world beyond.

My parents insisted on taking me to California. The expense of three plane tickets, not to mention the hassles of getting to the airport and back, made it obvious that they would drive me there. Our family was used to long journeys west, but this would be the first time any of us made it all the way to California. Connie had school, and Gary was working full time so it was just Mom, Dad, and me packing into the car for the long journey to my future.

As we began our five-day drive to California, I asked my parents to stop at the sign outside of town so I could pose for one last photo and say goodbye.

The silly, rebellious teenage me, despite holding no malice toward the city that raised me, stood under the Neillsville sign and recited the Book of Mark:

And whosoever shall not receive you, nor hear you, when ye depart thence, shake off the dust under your feet for a testimony against them. (Mark 6:11)

Although I would return, briefly, for Christmas and then again the following summer, my Neillsville life was over. It would be decades before I returned with eyes that were mature enough to understand what I left behind.